The first thing I notice is a feeling of weight on my face. Followed by a sensation of standing in boundless space. A monochrome 360-degree vanishing-point vista winks into view. I look around, blinking into the far distance and very quickly my adjusting eyes fill with grit… Welcome to the weird world of 21st century virtual reality.

What does it feel like to step inside the latest hugely-hyped tech reboot? Something like — I imagine — the sensation you might experience had you been swallowed by a 1960s television set, perhaps after spending too many hours staring into its grainy screen. There’s even an electrical umbilical tethering you to the wall. No reality here, then, just pixels every which way you look.

Does it feel like the future? Frankly no, it feels strangely retro.

Wind back the clock an hour and the pixels have fallen away from my eyes and I’m sitting, untethered, on an actual sofa, looking at a real human being in retinal high definition – HTC’s Drew Bamford, corporate VP and head of its Creative Labs team of product designers. Also a VR evangelist, as I am about to find out.

“We were just talking about you people,” he says, looping in the PR sitting to my left with a knowing side-eye, after I confess my VR scepticism. They both laugh – with a little too much hard-pumped enthusiasm. HTC has a lot riding on the success of the Vive. And therefore on the virtual reality reboot, generally. Sceptics aren’t exactly welcome in this brave new world.

Bamford is of course a paid up member of the ‘VR is the future’ club – but then he has to be, given the precarious fortunes of HTC’s business. The mobile maker has been hammered in the competitive Android OEM space in recent years and is banking on its VR partnership with games publisher Valve to revive its device making business. The wider consumer electronics industry is also on the hunt for the next smash-hit success – as the smartphone market reaches saturation point. Although few others stepped into VR as early as HTC or have yet bet so big.

And so we arrive at the HTC Vive, which will ship to buyers next month, on April 5, priced at $800 plus the price of a powerful enough PC needed to drive the VR experience. This cutting-edge yet somehow retro-looking headset is undoubtedly why I have been afforded half an hour of Bamford’s time here at Mobile World Congress. VR, we’re told by the ceaseless tech PR drum-beat, is going to be 2016’s Big Thing. HTC is a clear believer; one of relatively few companies throwing a headset into the VR ring at this nascent stage. Although more are getting involved — at least at the more budget smartphone-powered ‘mobile VR‘ end of things.

But then considering how crowded and viciously thin the margins in the smartphone space nowadays (iPhones excepted), the barren hinterlands of VR probably induced sensations of wild relief in HTC’s management. ‘Here, finally, is a space where we can stand out without needing to wield Samsung-sized marketing budgets,’ they might well have thought.

Safe to say, ‘sick of smartphones’ is probably one of the more concise explanations for the latest attempt to kindle a mainstream VR market. And this time the virtual reality is for real! Or so they’d have us believe.

“I come from a background in consumer electronics products, primarily, design. And so I’ve worked on a lot of diverse products but since I got to HTC almost nine years ago I’ve worked almost exclusively on phones. So this is for me a little bit like getting back to my roots and working on different kinds of consumer experiences,” says Bamford, discussing his personal excitement for VR and – therefore – for HTC’s Vive. (And, by implication, his fatigue with phones.)

“But for some of the team it’s kind of a new thing — they were hired as phone people and now they’re like learning about designing stuff you wear on your body or immersing people in VR.

“For me it’s a little bit like going back to 2006 when we were pioneering smartphone experience design and there was an opportunity to establish new patterns. To discover new ways of interacting. We’re actively doing that, especially in VR right now — which is a lot of fun.”

“We’re creating a totally alternate reality in VR. And there’s a lot to do,” he adds “There’s a lot to figure out. But we’re taking it step-by-step, right. I have no doubt that the things that we’re designing today will seem quite antiquated in a couple of years. But that’s just how the process works.”

The things that we’re designing today will seem quite antiquated in a couple of years.

Here at MWC, the world’s largest mobile industry focused conference, HTC’s booth is symbolically split in two, divided across a carpeted thoroughfare that funnels a continual parade of suits back and forth. One half of the booth displays a smorgasbord of mobile hardware: different smartphones and connected devices (such as the wearables HTC is making in partnership with Under Armour) curated into what amounts to exhibition of well made but sadly under-appreciated hardware.

On the other side it’s pure, minimalist VR. Here the Vive branding looms large, watched over, here and there, by HTC’s neon green lettering. Over the four days of the conference a steady stream of men queue for a chance to don a headset and sit in chairs blasting virtual stuff in partially screened booths or prancing around in carpeted display rooms with painterly backdrops probing the Vive’s room-scale claims. Most of these test bays can be peered into by anyone who happens by.

HTC’s brave new public face, then, is the strange spectacle of besuited blokes blindly gesticulating into thin air. Here’s To Crazy, indeed.

It has already taken a long time for HTC to arrive at this point. At MWC last year HTC’s Peter Chou announced its partnership with Valve and gave the first official glimpse of the Vive’s distinctly dimpled headset. Chou has since been moved out of the company, passing the CEO role to chairperson Cher Wang who earlier this year described VR as its priority. Implication being that smartphones are now playing second fiddle to the virtual future it’s hoping to build with Valve. And yet VR evangelists can only dream of a profitable business comprised of pixelated ‘experiences’ at this oh-so-nascent stage. The hype is real, certainly. The profits are – for now – tantalizingly imaginary.

Bamford’s job, then, is to talk up the potential of VR. And talk he does.

“I believe outside of gaming there are all sorts of incredible applications for this technology,” he tells TechCrunch. “For example one area we’re working quite a lot in is tools for designers and engineers. So we’re working with partners like Dassault Systemes in France to figure out how to let automotive designers for example visualize cars in VR. So that they don’t have to build these full scale clay mock ups. Because it’s so important to be able to get a sense of the scale of the product. And see different sight lines and things like that, and it’s not something you can easily do on a monitor. Many of these automotive companies have been building these giant cave systems that cost millions of dollars to install. And now they can basically replace it with a $799 Vive.

“So that’s exciting. And of course the other area — from a design and engineering standpoint — that’s interesting is architecture. Because it’s so much about inhabiting a space. And feeling… different sight lines, feeling what it’s like to move through a space, which is the perfect application for a room scale device like Vive. It’s not something you can really get an experience of on a monitor.”

“We’re working with medical partners like Surgical Theatre,” he continues. “Which is doing pre-visualization of tumors for brain surgeons. That kind of application — it’s information the surgeon couldn’t normally get; a 3D view of the tumor they couldn’t normally get. So it may be inconvenient to put this thing on your head or dorky or whatever but in an environment like that of course you’re willing to do it.”

Specialist enterprise use-cases are one thing, where VR can blend in as just another task-specific work tool. But that’s not a mainstream market to rival the massive appeal of smartphones, which is of course the trick every mobile maker yearns to be able to repeat. The raging success of the smartphone is, however, a very hard act to follow.

Would anyone really want to spend all day in VR? Isn’t that just dystopic? “Don’t count it out,” says Bamford, suggesting certain types of information-dense office jobs – like finance workers – could, for example, replace their banks of monitors with a VR headset. “Certainly in the office I can see a lot of people wearing a VR headset all day at their desk.”

Certainly in the office I can see a lot of people wearing a VR headset all day at their desk.

Which sounds like one way for office drones to escape drear cubicles — in an almost Matrix style real-world VR plot twist…

“One of the things that I’m personally really excited about is content that you could say it’s not really a game but content that provides people with experiences they couldn’t normally get in the real world,” Bamford continues. “For example one of the most popular demos we have is Wevr’s The Blu… It’s an underwater experience where there’s a blue whale. So it’s not really a game actually, it’s just you’re experiencing being underwater in an environment that most people will never see in real life. I think there’s a huge opportunity to do more of that kind of experience. For example you could visit the top of Mount Everest or journey back in time to be in the Roman Colosseum. Just being in a place and exploring a place I think can be really compelling in VR.”

“I agree a smartphone is a more everyday product, for sure,” he adds, picking up the earlier train of thought. “It’s something you can carry with you everywhere and you can use easily in public without looking like a cyborg… But I would not discount the fact that eventually some types of people will replace their desktop monitor with a VR headset. Depending on what you’re doing. Already we have partners like Envelop that are building systems that allow VR developers to develop in VR so they don’t have to have a monitor — they just use a headset.

“Certainly people in the VR industry will do that but I think even outside of that you’ll see — you could imagine somebody in the finance business. These guys right now have six Bloomberg screens in front of their desk. They could easily replace that with an HMD [head-mounted display] in order to see more data — which is what it’s all about.

“And beyond that I think as the technology is miniaturized, as VR and AR [augmented reality] converge, you’ll get VR-like experiences with a significantly less alienating physical experience, right. You won’t necessarily have to put an HMD in front of your eyes in order to experience 3D content… From the AR side, there’s going to be this kind of portable VR that maybe is less intrusive, just looks like glasses or something. But certainly in the office I can see a lot of people wearing a VR headset all day at their desk.”

Is he envisaging a much lighter weight wearable in future? Or something else? “You’ll have holographic displays,” he suggests. “Where you get similar content experiences. Where all the software work we’re doing can translate into that but it’ll be a totally different hardware delivery system over time. I mean this is years out, but maybe not too many years. Maybe in five years you’ll be doing something like that.”

VR without the need to don a headset starts to sound a lot less like a separate industry, IMO – and more an adjunct to the smartphone market. After all, a holographic smartphone would still be a smartphone, just one with added VR smarts. Much like mobile makers a few years ago trying to push 3D screens. (A push that fizzled out just as quickly.)

Not that HTC is in VR to be a VR purist of course; it just needs to sell product – whatever shape or form that takes. Hence it’s already crossing the VR/AR streams by adding a front-facing camera to the Vive headset that allows for some real-world ‘content’ to bleed into the wearer’s virtual world. In part this is a helpful safety feature, so users can switch to the Vive’s rotoscope-style view of what’s actually going on in the room around them – say, to avoid treading on sharp objects left on the carpet. Or to sneak a glimpse at what their friends are up to. So there’s an element of the AR/VR blend that presumably helps reduce VR FOMO too.

Fear of missing out has explicitly driven another Vive feature addition: phone services, which will enable users to take and make calls when in VR. Bamford says this feature was added after feedback from testers found people were worried they were missing on real-world communications with their friends. Which, given how much people love their smartphones, messaging and social media apps should probably have been abundantly obvious. Even pure, unadulterated escapism from real life needs to be diluted to accommodate constant connectivity needs – and so Vive has both an eye on and line back into the real world.

When they’re in there for a while we found that people start to wonder if they’re missing things.

“One of the things that we discovered in our research is that people love the idea of being immersed in VR and feeling like they’re in a completely different place and not worrying about the real world. But at the same time when they’re in there for a while we found that people start to wonder if they’re missing things. Are they missing calls? Are they missing messages from there friends, etc. And so the phone connectivity is an attempt to solve that problem. So when you’re in VR you can get a phone call — you can talk on the phone. You can get text messages, reply to text messages — so you can enjoy VR without worrying that you’re missing what’s going on in real life.”

The need to ensure that VR users still feel connected with their real-world relationships when they’re escaping into virtual worlds has presented one specific design challenge that Bamford says HTC is still wrestling with: how to inject real world missives/notifications into VR without ‘breaking presence’, as it’s known. (See the end of this post for a short VR glossary.)

“We don’t want to break presence. That’s the central tenant of VR. You don’t want to take people out of the experience. So we try to make it as non-intrusive as possible,” he explains. “The way it works right now is you can be in any VR experience and you get a notification that appears in 3D space that says you’re getting a call or text message. And then if you want to act on that notification you bring up a pretty standard UI that lets you do things like answer the call or send a canned response to a text message.”

I jokily suggest that maybe emails should appear as white rabbits hopping into view. “That could be the next version — so an Alice in Wonderland style,” laughs Bamford. “Different animals could trot into the scene… ”

“That’s the kind of native VR integration that eventually we’ll get to, I think. But at the moment it’s quite a bit simpler than that,” he adds. “It’s been a challenging part to design. And we’re still, frankly, tuning that to make it as seamless as possible. But we’re getting there.”

Standard UI elements can appear as wireframe interfaces within Vive’s virtual spaces to make them stand out in more richly rendered environments. Engaging with these menus means using the bundled controllers to point, swipe and click. These twin sticks – one held in each hand — have multiple buttons and a swipe-pad apiece, allowing them to stand in as virtual hands or guns or shields, at one moment, and then act as a point and click device to navigate menus the next. The controllers are lightweight and ergonomic enough that at times it’s possible to forget you are holding a couple of oddly shaped pieces of black plastic and believe you are really hefting that translucent shield or pair of guns.

Depending on the quality of the content, of course.

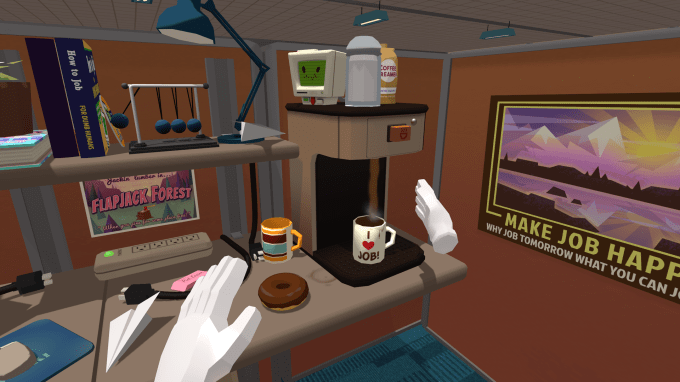

HTC’s selected demos did the best at showcasing the immersive potential of VR, as you’d expect, but I was less convinced by some of the content that will be bundled with the Vive. In one game, Job Simulator, the controllers appear as a pair of cartoonish white hands — and trying to pick up objects in the virtual office environs using these mitts felt hopelessly clumsy. But perhaps that was the point? Playing a game where you pretend you’re inept in a simulation of a fake office job where everything appears ridiculously cartoonish and nothing really needs to be done is presumably someone, somewhere’s idea of fun.

Still, on the content front, VR offers the prospect of something worse than mild tedium – out and out nausea. On the risk of this, Bamford says: “We’re very confident that our technology will make you the least sick of any VR experience.”

We’re very confident that our technology will make you the least sick of any VR experience.

And in my own half-hour or so demo of the Vive that claim at least stood up. I came away without feeling nauseous. But did experience a feeling of grittiness in the eyes, much like if you’ve been straining to look at a poor quality screen or trying to read in the dark or have spent too much time exposed to UV lights. I was also being careful about how I moved around — avoiding making any fast or jerky movements. When it comes to VR, FON (fear of nausea) and FOLLAD (fear of looking like a dork) are at least as potent as FOMO, IMO.

“We do think with 90fps, with very low latency, with low persistence displays, with millimeter precision tracking that we’re offering you’re very unlikely to get sick with Vive,” says Bamford – although he quickly follows this up with the caveat “if the content is designed correctly”.

Has he ever personally felt nauseous while testing Vive? Only when something has gone wrong, he says – such as when using a development prototype that isn’t working properly. Then he’s felt “dizzy”.

Even so, he concedes there are a lot of variables in play — some of which HTC/Valve can’t control, given they’re leaning on “hundreds” of developers to create the ‘mind-blowing’ content needed to lure people into their virtual spaces.

“There are a lot of variables in how you design the experience. And some experiences are more likely to make you feel ill than others. So one of the things we’ve discussed and debated is whether there should be some kind of rating system for propensity to get sick from a particular type of content. But it’s quite controversial because you don’t want to turn people off of certain content and everybody has a very individual sense for how they’ll react so we haven’t gotten too far on that yet. But I think that could happen, I think there could be a rating system where on a scale of one to five this is more or less likely to make you feel less nauseous.”

“This is the reason we really need a way to filter the best content into our experience and make sure that bad content doesn’t get onto the market because it could poison the well,” he adds.

Eyestrain aside, the strongest negative sensation I experienced from trying the Vive (in what, it should be emphasized, was HTC’s own controlled demo environment, being shown demo content they were choosing) was a feeling of being constrained. But given this (gen-1) VR experience requires wearing a weighty headset over your eyes while walking in a small space tethered to a cable that easily tangles with your feet it’s hardly surprising to come away feeling more fettered than liberated. ‘Room-scale VR’, then, translates to being able to take a few tentative steps in a given direction. Provided there isn’t a wall in the way.

Another demo — Google’s Tilt Brush, a painting program that lets you paint trails of virtual paint in the air and which will also be bundled free with Vive — ended up making me feel a little claustrophobic after I ended up painting myself into a cage made of glowing orange streaks. Thing is, the elements you see within VR are always at risk of invading your personal space; because of course there’s no screen barrier here, you are right inside the content – so it’s possible that, rather than feeling liberated within boundless virtual space, you end up feeling hemmed in and/or mobbed by pixels. And sure, you can always walk right through the fourth wall (as it were), passing through these virtual objects since they’re not — haha! — real. But since they look solid and are designed to trick your brain into belief, well your perception of how much space you have to move around shrinks to fit them.

At another point during my Vive demo I materialized partially inside a moon floating at about head height. Discombobulating is probably the appropriate word for that. And not a little ironic that I had to take a few side-steps to try to find a little personal space in what was a virtual rendering of infinite outer space… Feelings of being trapped inside virtual infinity? Yep, those are the weird sentences you end up typing when writing about VR.

Talking of moving around, Bamford says that one of the custom elements HTC’s Vive might let users switch on and off, depending on how sensitive they are to faster animations within VR, is a teleportation feature that lets people “zap themselves” (as he puts it) from different locations to avoid needing to actually walk to places given that their (physical) play space has some hard limits.(The Vive’s tracking system maxes out at a space that’s 15 feet by 15 feet.)

“The safest way to do it is just by blinking your location to a new place. You’re instantaneously transported. But actually some people’s preference – including my preference – is to do really fast transition, animated transition… Some people call it ludicrous speed so it’s this really fast animation. And that doesn’t bother me at all. And actually for me I believe it provides you a lot more context because you don’t get as disoriented when you’re moving. You understand how you got there. But for some people it actually makes them pretty nauseated.”

“So this is the kind of thing where we’re working on ways for people to turn stuff like that on and off, depending on how sensitive they are. It needs to be a personal preference,” he adds.

There’s also a lot of internal debate at HTC about another element of VR design: whether people will want to have realistic looking (i.e. selfie-style) avatars, according to Bamford. Or whether they will want to go full-blown fantasy character stylee – and look like a cartoon dog or something. This question does not arise so much for solitary play but rather for social VR — which Bamford is convinced will be a thing. People will want to get together virtually when they are physically apart, he asserts.

As much as you think of VR as a very solitary thing where you’re just wearing a headset in your basement, people want to go into that virtual world and then interact with other people.

“People do want to be social in VR. As much as you think of VR as a very solitary thing where you’re just wearing a headset in your basement, people want to go into that virtual world and then interact with other people, so that’s a huge area of investigation for us.

“The social element is a little funny. But we’ve looked at scenarios like, for example, sitting next to your significant other on a couch and you’re both wearing headsets watching a VR film. I think that will happen,” he continues. “You’ll still be able to interact with the person it’s just that you’re in VR.”

Interact virtually sure, just don’t lean in for a kiss. Smashing VR headsets together doesn’t sound at all fun.

How many marriages is VR going to ruin, I joke. “At the same time how many people will meet in VR and be perfectly happy?” he counters. So perhaps VR can save Second Life too. (Yes, Linden Labs is already taking a close interest in the tech.)

Or perhaps it will power the next big thing in online dating. (Albeit, the burning question then would be: in VR would anyone be able to tell if you’re a dork in real life too?)

On the avatar design point, Bamford says the internal debate continues. “We’ve looked, for example, at technologies that would allow you to easily scan your own face and create an avatar that looks like you. But it’s unclear if anybody really wants to do that. Or certainly if you do scan yourself everybody kind of agrees that you’re going to want to be able to improve/touch up your avatar. So it looks sort of like you but a better version of you.”

How photorealistic can VR avatars be made to look at this point, with the current gen tech? “It can look like you but then the challenge is animating the eyes and the expression around the eyes and the mouth, so that it actually looks realistic is quite difficult,” he says, admitting there is still an “uncanny valley problem”.

“Probably you will look like a creepy version of you,” he concedes.

It’s a very strange world you’re building here, I observe. “Well someone has to do it,” he says, before asserting more emphatically: “It will improve dramatically over time. And I think it’ll be pretty quick, the improvements. Already for example we’re working with partners that will take just the audio stream from your voice and automatically animate your mouth to match the words that you’re saying. And it’s still a little bit funny looking but eventually as the rigging gets better on the characters and as the speech recognition gets better it could be do-able.”

So are people going to be wowed by the Vive’s gen-1 VR experiences or is it going to take a few iterations — and some of the refinements Bamford has been talking about — to hone the hardware and software to a point where the experience is more lifelike blow-your-socks off and less grainy/creepy tethered in an uncanny valley?

“I absolutely think people will be wowed,” says Bamford. “I’ve been working in technology for a long time — 20 years. And I’ve worked on a lot of stuff that people thought was ground breaking at the time but I’ve never worked on anything that got the reactions that VR gets. I mean I’ve seen so many people do the demo and literally have to [sit down… because of] the sensory overload.

“It’s quite impressive the reactions you get out of this. I’ve actually never seen anybody after a demo that was not — that didn’t say it was in some way mind blowing.”

Sensory overload from demos of peaceful blue whales is one thing but there are likely to be more sensitive considerations when it comes to certain types of VR games and experiences. On this point, Bamford tells an anecdote about the first time he played the zombie game, Arizona Sunshine, in VR.

“Nobody told me how to pick up the gun and use it so I didn’t know how to protect myself. And what happens is these zombies come at you and then just start hitting you with their limbs. And it was horrifying, actually.

I think there do need to be some kind of warnings depending on the content type – ‘this can seriously mentally disturb you’.

“So you can imagine people actually being really scared playing some of these things so I think there do need to be some kind of warnings depending on the content type – ‘this can seriously mentally disturb you’, actually. If you’re not prepared for the content. So you have to know what you’re getting into. And I think there will have to be some education around what sorts of content’s appropriate to different people.”

“But for people who want to be scared – and there are a lot of people who want to be scared, it will be the most satisfyingly horrifying experience you can imagine,” he adds.

Bamford does not stick around to see me do my Vive demo. But he does have a few words of advice for what I should do if I feel like I’m turning a little green.

“Remember,” he tells me, “you can always close your eyes.”

Amen to that.

Leaving the conference later in the day my VR experience dissolves into the Barcelona sunshine and a residual thought surfaces from the depths of my brain: wow, reality — now that really does look amazing…

The weird words of weird worlds: A short VR glossary

HMD – head mounted display. Aka the VR headset

nose gasket – interchangeable inserts inside the Vive headset that are designed to ensure it fits snuggly around the user’s face/nose

360 degree head-tracking – a VR system that can track a user’s head howsoever it moves

room-scale VR – the ability to walk and be tracked around a space while in VR, rather than needing to sit or stand still. Does still require the headset to be tethered to the PC that powers the VR

Lighthouse – the light emitting system inside the Vive’s twin base stations which power its 360-degree head tracking by determining the position of the wearer’s head. The base stations sweep the room with lasers while multiple photosensors on the headset keep time between light sweeps – using the numbers to calculate the position of the user’s head

Chaperone – a safety feature within Vive that bleeds a wireframe view of real-world objects into the Vive’s virtual world to help prevent the user from hurting themselves by, for instance, walking into walls

low persistence display – a technique to reduce motion blur/judder as it is perceived within VR by illuminating pixels for a short time only, when they are correctly aligned for the user’s viewpoint, and switching them off immediately the viewpoint shifts

presence – the feeling of immersion that a user of VR experiences; designers aim never to ‘break presence’, as they term it

experiences – VR content that’s not designed as a game per se but is rather intended to evoke feelings or emotions on account of the spectacle/encounter the user experiences

uncanny valley – the challenges of animating humanoid VR avatars so they seem realistic, rather than creepy, such as animating expressions around the eyes or lips to sync with spoken words

social VR – mingling with other VR users in a virtual environment as opposed to escaping into a solitary other worldly VR experience

pre-visualization – the ability to view something in simulated 3D in VR before actually viewing the object in real life

ludicrous speed – a locomotion mechanism that animates a VR user’s transition from one place to another in a game world to help preserve location context and reduce disorientation. Can cause nausea

Comments are closed.